The debate of whether the Parthenon Sculptures held in the British Museum should return to Greece remains controversial through the years. The sculptures are the subject of one of the longest cultural rows in the world and the views on the fate of the treasures differ.

Table of Contents

I am Greek and I wanna go HOME

The return of the marbles back to Athens remains the priority of the Ministry of Culture of Greece which frequently conducts campaigns to provide publicity to the subject while British museum claims the legal and rightful ownership of the Marbles. Displayed at the London museum since 1832, their return has been demanded by Greece for much of that time, leaving the two countries stuck in a sometimes testy stalemate. It is now time “to do something qualitatively different”, Victoria Hislop suggests

There’s an aesthetic case for unification, somewhere, and a geographic case for reunification in Greece. No god or goddess should be made to bear the indignity of headlessness, and no visitor should be needlessly deprived of viewing a masterpiece that’s actually in one piece.

Molly Roberts, Editorial Writer, Washington Post

The Acropolis Under Siege

The Parthenon was constructed between 447 and 432 B.C.E., a period of artistic and military triumph considered the golden age of ancient Greece. The Athenians had expelled a Persian invasion prior to the temple’s construction, preserving their democracy, and the project became symbolic of the epoch-defining battle.

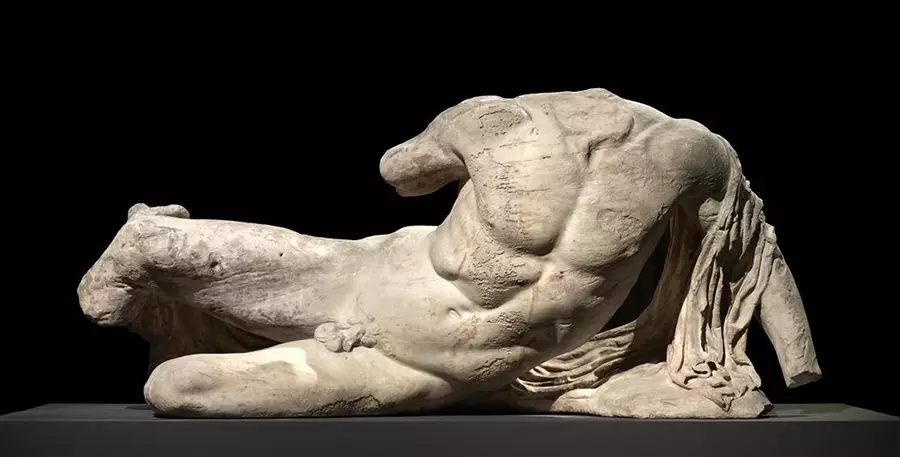

Vividly painted sculptures and decorations adorned the lavish temple to the city-state’s patron deity, Athena, the goddess of wisdom and war. Ninety-two carved metopes, square blocks placed between the columns, adorned the exterior walls of the Parthenon, depicting the Trojan War and other mythological battles.

Along the entire length of the Parthenon’s inner chamber was a frieze likely depicting a procession to the Acropolis. Two sculptured pediments depict the birth of Athena and the conflict between the goddess and Poseidon over the land which would become Athens.

But the temple fell into a derelict state following the occupation of the Ottoman occupation of Greece in the 15th century. Ottoman troops repurposed the Parthenon as a mosque (a minaret was even constructed). But around half the site was destroyed in an ensuing battle between the Venetians and the Ottomans. In September of 1687, a Venetian mortar struck the monument, causing an explosion that destroyed its roof but spared its pediments.

British press publicized the vulnerability of the monument—“It is to be regretted that so much admirable sculpture as is still extant about this fabric should be all likely to perish from ignorant contempt,” the English antiquarian Richard Chandler wrote in 1770—encouraging western travelers to pillage its treasures in the interest of preservation. Their legal justification was tacit approval from Ottoman authorities.

The former British ambassador to the empire, the Scottish nobleman Thomas Bruce, seventh Earl of Elgin and 11th Earl of Kincardine, had greater ambitions. In 1799, amid Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt, he was sent back to Greece to foster closer relations with the Ottoman sultan Selim III.

He was instructed to survey and create casts of the country’s great monuments, so he brought with him a team of British artists led by painter Giovanni Battista Lusieri. But by then, it was difficult to approach the Parthenon and Ottoman troops demanded hefty daily payments for access. Already strapped for funds, Elgin directly appealed to the sultan for a firmen, or special permission, for his project to commence.

On July 6, 1801, the sultan issued the following firmen: “When they wish to take away some pieces of stone with old inscriptions and figures, no opposition be made.” Elgin interpreted this to mean he and his team could not only create copies of the monument but dismantle and export any pieces of interest.

Some of the present restitution debate has focused on Elgin’s interpretation of the firmen. A major 1967 study by British historian William St. Clair concluded that the ambiguous language more likely referred to items uncovered during excavations, not the Parthenon façade itself.

Elgin’s team removed 15 metopes, and 247 feet, or around half of the surviving frieze, including a female sculpture from the portico of Erechtheion and four fragments from a smaller temple to Athena Nike also located on the Acropolis. In 1803, the collection was loaded into some two hundred boxes and transported via the port of Piraeus to England.

The Marbles Arrive in London

Elgin imagined the Marbles would be used for public display and intended to reconstruct part of the Parthenon. The Venetian sculptor Antonio Canova was even volunteered for the commission. Canova, however, rejected the possibility, stating that “it would be a sacrilege for any man to touch them with a chisel.” In fact, at that time, public opinion in London was divided on the propriety of having removed the marbles from Greece.

One of the most vocal critics was the Romantic poet Lord Byron, whose narrative poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage decried British imperialism, and called the removal of the marbles the “last poor plunder.” Byron alludes to Elgin in his annotations of the poem with epithets like “spoiler,” “robber,” and “violator.”

However, not all were moved by the poet’s protests: enormous crowds flocked to see the marbles in 1807 when Elgin installed them in a house near Piccadilly in London. Public interest prompted the British government to consider Elgin’s offer to sell the marbles to the national collection. Despite his titles, Elgin was in serious financial straits after personally covering the cost of shipping the sculptures to England. Including bribes for safe passage, the total price was £74,000—equal to more than $1 million today. In 1816, Parliament created a commission to assess Elgin’s offer that priced the marbles at £35,000. The sale was approved by a margin of two votes.

In 1832, the marbles were relocated to the Elgin Room in the British Museum—the same year Greece won independence from the Ottoman Empire. Successive Greek governments have petitioned for the return of the works. In the 1980s, the government formally asked the British Museum to repatriate the marbles, citing the fact that authorization was given for their removal by an occupying empire, not the Greek government.

Bestselling British Author Victoria Hislop Says: Do the Right Thing

For many years, I sat on the fence in the debate over where the Sculptures truly belonged. As a child I was regularly taken to the British Museum and marveled at the many majestic and ancient sculptures that towered above my head. I, like most British children of the 1960s, felt it was our birthright to walk through this imposing building and learn about the history and culture of civilization. It never crossed my mind (nor most people’s in those days) that many of those things were removed against the will of their countries of origin.

The Sculptures were called “the Elgin Marbles” in those days (at least that has changed) and I for one happily believed that Lord Elgin (a man with a posh title, so surely an upright chap?) had “saved” the sculptures for posterity and brought them to England for a new audience to appreciate (because, surely, the Turks did not). History was so simple for British children in those days. Our history books were full of heroic victories and we believed that the British Empire had brought great benefits to many different parts of the world. Bringing objects of both artistic and spiritual value from many other countries, all of them poorer than ourselves at the time, seemed perfectly normal.

Nowadays we question all of that. Many in Britain are reconsidering the actions that were taken in the past by the British. We can’t undo most of them (slavery being the most enormous and terrible example) but already we are apologizing for some of the many mistakes made by our ancestors. Even the gesture of doing this is important.

Going back to the Sculptures specifically, this was a case for me of questioning all the facts and circumstances surrounding how they ended up in a gloomy, badly lit gallery in the British Museum, thousands of miles from the translucent Hellenic light where they were created.

I read everything I could find (including Christopher Hitchens and Geoffrey Robertson) and went from darkness into light, realizing that much of the Elgin story that many in the UK believe is entirely untrue. He was given permission in the form of a letter (not an officially stamped Firman from the sultan as so many think) to take impressions and drawings of the sculptures so that they could be reproduced to decorate his new house.

He was not given permission to violently hack and saw them off the building, a task which took 300 men an entire year to achieve and required massive bribes to local guards. Elgin’s desire to have these originals for his private house was only thwarted when he finally returned home and found himself with massive debts. The British Museum paid him £35,000 (less than half his expenses for removal and transport) to help resolve his money problems and pay divorce expenses. The one unquestionable thing in this long debate is that the British government did hand over money for these priceless objects. But not to their rightful owners.

Many years after the acquisition, Henry Duveen (another figure with his own shadowy story) gave money for the gallery where they now live and instructed them to be scrubbed with wire wool to make them whiter, an act which by anyone’s standards is seen as an act of destruction, not conservation today.

There is not enough space to express all my emotions on the subject of the mistreatment of these beautiful objects but, needless to say, a small amount of reading was enough to shift my opinion completely and Boris Johnson’s interview last year for a Greek newspaper in which he implied that the Sculptures would never go back to Athens spurred me to join the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles, a group which passionately and continuously lobbies for their aim. I am now one of at least 59% of the British population who believes that the Sculptures should be returned to Athens.

Not Just an Epilogue

The politicians and museum trustees and directors on both sides are generally obliged to use polite and careful language and I respect that. It’s how it should be. I am a member of the public, however, and perhaps can use stronger vocabulary. For me, Elgin’s action was a simple story of theft. I am massively embarrassed by it and the British Museum’s stubborn and outdated stance on the matter.

This is a museum which has 8 million objects in its ownership, of which only 80,000 are on display (1 percent!). As well as the moral arguments, there are the practical ones. They will not be short of other objects to display. And there will be rejoicing in the streets, not just of Athens but of London too. Once British politicians fully understand this, I believe the tidal wave of opinion will be irresistible. It’s a matter of them using their hearts as well as their minds and, quite simply, doing the right thing – and recognizing that history itself will see them doing it too.

Related Read:

How Did the Parthenon Marbles End Up in the British Museum?

Doing the Right Thing with the Parthenon Marbles

19,150 comments

Для эффективного продвижения можно купить базы xrumer, подобрав оптимальный вариант.

Для оперативного вирішення фінансових питань чудово підходить кредит на карту, адже гроші надходять майже миттєво. Не потрібно їхати до банку чи збирати довідки.

психолог онлайн консультация россия

выбор психолога онлайн

Ищете seo аудит? Gvozd.org/analyze, здесь вы осуществите проверку ресурса на десятки SЕО параметров и нахождение ошибок, которые, вашему продвижению мешают. Вы ознакомитесь с 80 показателями после анализа сайта. Выбирайте в зависимости от ваших задач и целей из большой линейки тарифов.

На сайте https://filmix.fans посмотрите фильмы в отличном качестве. Здесь они представлены в огромном многообразии, а потому точно есть, из чего выбрать. Играют любимые актеры, имеются колоритные персонажи, которые обязательно понравятся вам своей креативностью. Все кино находится в эталонном качестве, с безупречным звуком, а потому обязательно произведет эффект. Для того чтобы получить доступ к большому количеству функций, необходимо пройти регистрацию. На это уйдет пара минут. Представлены триллеры, мелодрамы, драмы и многое другое.

Ищете рейтинг лучших сервисов виртуальных номеров? Посетите страницу https://blog.virtualnyy-nomer.ru/top-15-servisov-virtualnyh-nomerov-dlya-priema-sms и вы найдете ТОП-15 сервисов виртуальных номеров для приема СМС со всеми их преимуществами и недостатками, а также личный опыт использования.

На сайте https://satu.msk.ru/ изучите весь каталог товаров, в котором представлены напольные покрытия. Они предназначены для бассейнов, магазинов, аквапарков, а также жилых зданий. Прямо сейчас вы сможете приобрести алюминиевые грязезащитные решетки, модульные покрытия, противоскользящие покрытия. Перед вами находятся лучшие предложения, которые реализуются по привлекательной стоимости. Получится выбрать вариант самой разной цветовой гаммы. Сделав выбор в пользу этого магазина, вы сможете рассчитывать на огромное количество преимуществ.

Завод К-ЖБИ высокоточным оборудованием располагает, и по приемлемым ценам предлагает большой ассортимент железобетонных изделий. Продукция сертифицирована. Наши мощности производственные позволяют заказы любых объемов быстро осуществлять. https://www.royalpryanik.ru/ – здесь можно прямо сейчас оставить заявку. На ресурсе реализованные проекты представлены. Мы гарантируем внимательный подход к требованиям заказчика. Комфортные условия оплаты обеспечиваем. Осуществляем быструю доставку продукции. Открыты к сотрудничеству!

Ищете подбор футбольной академии в испании? Expert-immigration.com – это по всему миру квалифицированные юридические услуги. Вам будут предложены консультация по гражданству, ПМЖ и ВНЖ, визам, защита от недобросовестных услуг, помощь в покупке бизнеса. Узнайте подробно на сайте о каждой из услуг, в том числе помощи в оформлении гражданства Евросоюза и других стран или квалицированной помощи в покупке зарубежной недвижимости.

На сайте https://vipsafe.ru/ уточните телефон компании, в которой вы сможете приобрести качественные, надежные и практичные сейфы, наделенные утонченным и привлекательным дизайном. Они акцентируют внимание на статусе и утонченном вкусе. Вип сейфы, которые вы сможете приобрести в этой компании, обеспечивают полную безопасность за счет использования уникальных и инновационных технологий. Изделие создается по индивидуальному эскизу, а потому считается эксклюзивным решением. Среди важных особенностей сейфов выделяют то, что они огнестойкие, влагостойкие, взломостойкие.

На сайте https://auto-arenda-anapa.ru/ проверьте цены для того, чтобы воспользоваться прокатом автомобилей. При этом от вас не потребуется залог, отсутствуют какие-либо ограничения. Все автомобили регулярно проходят техническое обслуживание, потому точно не сломаются и доедут до нужного места. Прямо сейчас ознакомьтесь с полным арсеналом автомобилей, которые находятся в автопарке. Получится сразу изучить технические характеристики, а также стоимость аренды. Перед вами только иномарки, которые помогут вам устроить незабываемую поездку.

Ищете прием металлолома в Симферополе? Посетите сайт https://metall-priem-simferopol.ru/ где вы найдете лучшие цены на приемку лома. Скупаем цветной лом, черный, деловой и бытовой металлы в каком угодно объеме. Подробные цены на прием на сайте. Работаем с частными лицами и организациями.

На сайте https://xn—-8sbafccjfasdmzf3cdfiqe4awh.xn--p1ai/ узнайте цены на грузоперевозки по России. Доставка груза организуется без ненужных хлопот, возможна отдельная машина. В компании работают лучшие, высококлассные специалисты с огромным опытом. Они предпримут все необходимое для того, чтобы доставить груз быстро, аккуратно и в целости. Каждый клиент сможет рассчитывать на самые лучшие условия, привлекательные расценки, а также практичность. Ко всем практикуется индивидуальный и профессиональный подход.

Ищете медтехника оптом? Agsvv.ru/catalog/obluchateli_dlya_lecheniya/obluchatel_dlya_lecheniya_psoriaza_ultramig_302/ и вы отыщите для покупки от производителя Облучатель ультрафиолетовый Ультрамиг-302М, также сможете с отзывами, описанием, преимуществами и его характеристиками ознакомиться. Узнайте для кого подходит и какие заболевания лечит. Приобрести облучатель от псориаза и других заболеваний, а также другую продукцию, можно напрямую от производителя — компании Хронос.

Студия «EtaLustra» гарантирует применение передовых технологий в световом дизайне. Мы любим свою работу, умеем создавать стильные световые решения в абсолютно разных ценовых категориях. Гарантируем к каждому клиенту персональный подход. На все вопросы с удовольствием ответим. Ищете освещение для кафе? Etalustra.ru – здесь представлена детальная информация о нас, ознакомиться с ней можно уже сейчас. За каждый этап проекта отвечает команда профессионалов. Каждый из нас уникальный опыт в освещении пространств и дизайне интерьеров имеет. Скорее к нам обращайтесь!

На сайте https://numerio.ru/ вы сможете воспользоваться быстрым экспресс анализом, который позволит открыть секреты судьбы. Все вычисления происходят при помощи математических формул. При этом в процессе участвует и правильное положение планет. Этому сервису доверяют из-за того, что он формирует правильные, детальные расчеты. А вот субъективные интерпретации отсутствуют. А самое главное, что вы получите быстрый результат. Роботу потребуется всего минута, чтобы собрать данные. Каждый отчет является уникальным.

Центр Неврологии и Педиатрии в Москве https://neuromeds.ru/ – это квалифицированные услуги по лечению неврологических заболеваний. Ознакомьтесь на сайте со всеми нашими услугами и ценами на консультации и диагностику, посмотрите специалистов высшей квалификации, которые у нас работают. Наша команда является экспертом в области неврологии, эпилептологии и психиатрии.

На сайте https://www.florion.ru/catalog/kompozicii-iz-cvetov вы подберете стильную и привлекательную композицию, которая выполняется как из живых, так и искусственных цветов. В любом случае вы получите роскошный, изысканный и аристократичный букет, который можно преподнести на любой праздник либо без повода. Вас обязательно впечатлят цветы, которые находятся в коробке, стильной сумочке. Эстетам понравится корабль, который создается из самых разных цветов. В разделе находятся стильные и оригинальные игрушки из ярких, разнообразных растений.

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

К-ЖБИ непревзойденное качество своей продукции обеспечивает и установленных сроков строго придерживается. Завод располагает гибкими производственными мощностями, что позволяет выполнять заказы по чертежам клиентов. Свяжитесь с нами по номеру телефона, и мы с удовольствием ответим на ваши любые вопросы. Ищете завод жби сергиев посад? Gbisp.ru – здесь можете заявку оставить, указав в форме имя, телефонный номер и адрес почты электронной. После этого нажмите на кнопку «Отправить». Гарантируем оперативную доставку продукции. Ждем ваших обращений к нам!

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

лечение от наркотиков

наркозависмость

лечение от наркотиков

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

лечение от наркотиков

наркозависмость

лечение от наркотиков

лечение от наркотиков

помощь наркозависимым

наркозависмость

Hackerlive.biz – сайт для общения с профессионалами в области программирования и не только. Тут можно заказать услуги опытных хакеров. Делитесь своим участием или же наблюдениями, которые связанны со взломом сайтов, электронной почты, страниц и других хакерских действий. Ищете заказать взлом viber? Hackerlive.biz – тут отыщите о технологиях блокчейн и криптовалютах свежие новости. Постоянно информацию обновляем, чтобы вы о последних тенденциях знали. Делаем все возможное, чтобы форум был для вас максимально понятным, удобным и, конечно же, полезным!

лечение от наркотиков

наркозависмость

наркозависмость

лечение от наркотиков

наркозависмость

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

наркозависмость

лечение от наркотиков

наркозависмость

лечение от наркотиков

наркозависмость

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

наркозависмость

наркозависмость

Посетите сайт https://mebel-globus.ru/ – это интернет-магазин мебели и товаров для дома по выгодным ценам в Пятигорске, Железноводске, Минеральных Водах. Ознакомьтесь с каталогом – он содержит существенный ассортимент по выгодным ценам, а также у нас представлены эксклюзивные модели в разных ценовых сегментах, подходящие под все запросы.

Xakerforum.com специалиста советует, который свою работу профессионально и оперативно осуществляет. Хакер ник, которого на портале XakVision, предлагает услуги по взлому страниц в любых соцсетях. Он имеет безупречную репутацию и гарантирует анонимность заказчика. https://xakerforum.com/topic/282/page-11

– здесь вы узнаете, как осуществляется сотрудничество. Если вам необходим доступ к определенной информации, XakVision к вашим услугам. Специалист готов помочь в сложной ситуации и проконсультировать вас.

помощь наркозависимым

лечение от наркотиков

На сайте https://sprotyv.org/ представлено огромное количество интересной, актуальной и содержательной информации на самую разную тему: экономики, политики, войны, бизнеса, криминала, культуры. Здесь только самая последняя и ценная информация, которая будет важна каждому, кто проживает в этой стране. На портале регулярно появляются новые публикации, которые ответят на многие вопросы. Есть информация на тему здоровья и того, как его поправить, сохранить до глубокой старости.

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

Ищете понятные советы о косметике? Посетите https://fashiondepo.ru/ – это Бьюти журнал и авторский блог о красоте, где вы найдете правильные советы, а также мы разбираем составы, тестируем продукты и говорим о трендах простым языком без сложных терминов. У нас честные обзоры, гайды и советы по уходу.

наркозависмость

Visit BinTab https://bintab.com/ – these are experts with many years of experience in finance, technology and science. They analyze and evaluate biotech companies, high-tech startups and leaders in the field of artificial intelligence, to help clients make informed investment decisions when buying shares of biotech, advanced technology, artificial intelligence, natural resources and green energy companies.

Посетите сайт https://rivanol-rf.ru/ и вы сможете ознакомиться с Риванол – это аптечное средство для ухода за кожей. На сайте есть цена и инструкция по применению. Ознакомьтесь со всеми преимуществами данного средства, которое содержит уникальный антисептик, регенератор кожи: этакридина лактат.

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

На сайте https://www.florion.ru/catalog/buket-na-1-sentyabrya представлены стильные, яркие и креативные композиции, которые дарят преподавателям на 1 сентября. Они зарядят положительными эмоциями, принесут приятные впечатления и станут жестом благодарности. Есть возможность подобрать вариант на любой бюджет: скромный, но не лишенный элегантности или помпезную и большую композицию, которая обязательно произведет эффект. Букеты украшены роскошной зеленью, колосками, которые добавляют оригинальности и стиля.

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

T.me/m1xbet_ru – официальный канал проекта 1XBET. Здесь вы быстро найдете необходимую информацию. 1Xbet вас разнообразием игр удивит. Служба поддержки оперативно реагирует на запросы, заботится о вашем комфорте, а также безопасности. Ищете 1xbet рабочее зеркало? T.me/m1xbet_ru – тут рассказываем, почему стоит выбрать живое казино. 1Xbet много возможностей дает. Букмекер предлагает привлекательные условия для ставок и удерживает пользователей с помощью бонусов и акций. Отдельным плюсом является быстрый вывод средств. Приятной вам игры!

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

Компонентс Ру – интернет-магазин электронных компонентов и радиодеталей. Стараемся покупателям предоставить по приемлемым ценам большой ассортимент товаров. Для вас в наличии имеются: вентили и инверторы, индикаторы, источники питания, мультиметры, полупроводниковые модули, датчики и преобразователи, реле и переключатели, и другое. Ищете осциллограф? Components.ru – здесь представлен полный каталог продукции нашей компании. На сайте можете ознакомиться с условиями оплаты и доставки. Сотрудничаем с юридическими и частными лицами. Всегда вам рады!

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

Популярный портал помогает повысить финансовую грамотность, самым первым узнать интересующие новости, сведения из мира политики, банков, различных финансовых учреждений. Кроме того, имеются материалы о том, каким бизнесом выгодней заняться. https://sberkooperativ.ru/ – на сайте самые свежие, актуальные данные, которые будут интересны всем, кто интересуется финансами, прибылью. Ознакомьтесь с информацией, которая касается котировок акций. Постоянно появляются любопытные публикации, фото. Следите за ними, советуйте портал знакомым.

Посетите сайт https://allforprofi.ru/ это оптово-розничный онлайн-поставщик спецодежды, камуфляжа и средств индивидуальной защиты для широкого круга профессионалов. У нас Вы найдете решения для работников медицинских учреждений, сферы услуг, производственных объектов горнодобывающей и химической промышленности, охранных и режимных предприятий. Только качественная специализированная одежда по выгодным ценам!

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

На сайте https://sprotyv.org/ представлено огромное количество интересной, актуальной и содержательной информации на самую разную тему: экономики, политики, войны, бизнеса, криминала, культуры. Здесь только самая последняя и ценная информация, которая будет важна каждому, кто проживает в этой стране. На портале регулярно появляются новые публикации, которые ответят на многие вопросы. Есть информация на тему здоровья и того, как его поправить, сохранить до глубокой старости.

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

Ищете аудит сайта бесплатно онлайн? Gvozd.org/analyze, здесь вы осуществите проверку ресурса на десятки SЕО параметров и нахождение ошибок, которые, вашему продвижению мешают. Вы ознакомитесь с 80 показателями после анализа сайта. Выбирайте в зависимости от ваших задач и целей из большой линейки тарифов.

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

«1XBET» считается одной из самых популярных БК, которая предлагает огромное количество вариантов для заработка. А узнать об этом подробности получится на официальном канале данного проекта. Теперь он окажется в вашем кармане, ведь заходить на него можно и с мобильного телефона. https://t.me/m1xbet_ru – на портале вы отыщете актуальные материалы, а также промокоды. Они выдаются во время авторизации, на значительные торжества. Также имеются и VIP промокоды. Все самое свежее об этой БК вы узнаете на этом канале, который вам рад.

Auf der Suche nach Replica Rolex, Replica Uhren, Uhren Replica Legal, Replica Uhr Nachnahme? Besuchen Sie die Website – https://www.uhrenshop.to/ – Beste Rolex Replica Uhren Modelle! GROSSTE AUSWAHL. BIS ZU 40 % BILLIGER als die Konkurrenz. DIREKTVERSAND AUS DEUTSCHLAND. HIGHEND ETA UHRENWERKE.

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

Бизонстрой предоставляет услуги по аренде спецтехники. Предлагаем автокраны, бульдозеры, погрузчики, манипуляторы и другое. Все машины в безупречном состоянии и готовы к немедленному выходу на объект. Считаем, что ваши проекты заслуживают наилучшего – современной техники и самых выгодных условий. https://bizonstroy.ru – здесь представлена более подробная информация о нас, ознакомиться с ней можно прямо сейчас. Мы нацелены на долгосрочное сотрудничество с клиентами. Решаем вопросы профессионально и быстро. Обращайтесь и не пожалеете!

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

Как выбрать и заказать экскурсию по Казани? Посетите сайт https://to-kazan.ru/tours/ekskursii-kazan и ознакомьтесь с популярными форматами экскурсий, а также их ценами. Все экскурсии можно купить онлайн. На странице указаны цены, расписание и подробные маршруты. Все программы сопровождаются сертифицированными экскурсоводами.

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

Оригинальные запасные части Thermo Fisher Scientific https://thermo-lab.ru/ и расходные материалы для лабораторного и аналитического оборудования с доставкой в России. Поставка высококачественного лабораторного и аналитического оборудования Thermo Fisher, а также оригинальных запасных частей и расходных материалов от ведущих мировых производителей. Каталог Термо Фишер включает всё необходимое для бесперебойной и эффективной работы вашей лаборатории по низким ценам в России.

помощь наркозависимым

Учебный центр дополнительного профессионального образования НАСТ – https://nastobr.com/ – это возможность пройти дистанционное обучение без отрыва от производства. Мы предлагаем обучение и переподготовку по 2850 учебным направлениям. Узнайте на сайте больше о наших профессиональных услугах и огромном выборе образовательных программ.

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

На сайте https://fakty.org/ изучите свежие новости на самые нашумевшие темы. Они расскажут много нового, чтобы вы были в курсе последних событий. Информация представлена на различную тему, в том числе, экономическую, политическую. Есть данные на тему финансов, рассматриваются вопросы, которые важны всем жителям страны. Вы найдете мнение экспертов о том, что интересует большинство. Все новости поделены на категории для вашего удобства, поэтому вы быстро найдете то, что нужно. Только на этом портале публикуется самая актуальная информация, которая никого не оставит равнодушным.

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

Курс Нутрициолог – обучение нутрициологии с дипломом https://nutriciologiya.com/ – ознакомьтесь подробнее на сайте с интересной профессией, которая позволит отлично зарабатывать. Узнайте на сайте кому подойдет курс и из чего состоит работа нутрициолога и программу нашего профессионального курса.

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

Посетите сайт Digital-агентство полного цикла Bewave https://bewave.ru/ и вы найдете профессиональные услуги по созданию, продвижению и поддержки интернет сайтов и мобильных приложений. Наши кейсы вас впечатлят, от простых задач до самых сложных решений. Ознакомьтесь подробнее на сайте.

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

помощь наркозависимым

Посетите сайт https://allcharge.online/ – это быстрый и надёжный сервис обмена криптовалюты, который дает возможность быстрого и безопасного обмена криптовалют, электронных валют и фиатных средств в любых комбинациях. У нас актуальные курсы, а также действует партнерская программа и cистема скидок. У нас Вы можете обменять: Bitcoin, Monero, USDT, Litecoin, Dash, Ripple, Visa/MasterCard, и многие другие монеты и валюты.

https://www.rwaq.org/users/krylovavlasta2-20250802100456

Посетите сайт https://artradol.com/ и вы сможете ознакомиться с Артрадол – это препарат для лечения суставов от производителя. На сайте есть цена и инструкция по применению. Ознакомьтесь со всеми преимуществами данного средства, которое является нестероидным противовоспалительным препаратом для лечения суставов. Помогает бороться с основными заболеваниями суставов.

https://imageevent.com/yurahujan/vwzet

https://pxlmo.com/berbestplays1

https://paper.wf/ahihuebo/mavrikii-kupit-kokain-mefedron-marikhuanu

https://ucgp.jujuy.edu.ar/profile/ococeacohi/

Ищете гражданство швейцари? Expert-immigration.com – это профессиональные юридические услуги по всему миру. Консультации по визам, гражданству, ВНЖ и ПМЖ, помощь в покупке бизнеса, защита от недобросовестных услуг. Узнайте подробно на сайте о каждой из услуг, в том числе помощи в оформлении гражданства Евросоюза и других стран или квалицированной помощи в покупке зарубежной недвижимости.

https://pxlmo.com/padonvalez9k

https://ucgp.jujuy.edu.ar/profile/agodgohig/

https://hub.docker.com/u/ParishhappylifeParishgirl17

https://allmynursejobs.com/author/hannahsandershan/

https://odysee.com/@javadquinehr:69b98186c8fdb720163ffadd365ce0665c716410?view=about

https://community.wongcw.com/blogs/1125010/%D0%9A%D1%83%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%82%D1%8C-%D0%91%D0%BE%D1%88%D0%BA%D0%B8-%D0%9C%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D1%85%D1%83%D0%B0%D0%BD%D1%83-%D0%93%D0%B0%D1%88%D0%B8%D1%88-%D0%9E%D1%81%D0%BB%D0%BE

https://community.wongcw.com/blogs/1124220/%D0%A2%D1%8D%D0%B3%D1%83-%D0%BA%D1%83%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%82%D1%8C-%D0%9C%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D1%85%D1%83%D0%B0%D0%BD%D1%83-%D0%93%D0%B0%D1%88%D0%B8%D1%88-%D0%91%D0%BE%D1%88%D0%BA%D0%B8

https://www.brownbook.net/business/54138563/купить-экстази-кокаин-амфетамин-джидда/

https://bio.site/tuflwobihkei

https://git.project-hobbit.eu/gpjuofohn

https://allmynursejobs.com/author/kidshuudu/

На сайте https://glavcom.info/ ознакомьтесь со свежими, последними новостями Украины, мира. Все, что произошло только недавно, публикуется на этом сайте. Здесь вы найдете информацию на тему финансов, экономики, политики. Есть и мнение первых лиц государств. Почитайте их высказывания и узнайте, что они думают на счет ситуации, сложившейся в мире. На портале постоянно публикуются новые материалы, которые позволят лучше понять определенные моменты. Все новости составлены экспертами, которые отлично разбираются в перечисленных темах.

https://ytywabaxore.bandcamp.com/album/appear

https://www.brownbook.net/business/54134854/купить-кокаин-гоа/

https://community.wongcw.com/blogs/1125029/%D0%9A%D1%83%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%82%D1%8C-%D0%AD%D0%BA%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%B7%D0%B8-%D0%9C%D0%94%D0%9C%D0%90-%D0%9A%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%B8%D0%BD-%D0%91%D0%B5%D1%8D%D1%80-%D0%A8%D0%B5%D0%B2%D0%B0

https://kemono.im/cucyhedeh/antaliia-kupit-gashish-boshki-marikhuanu

https://hub.docker.com/u/wugskilllBrigettefive

https://ucgp.jujuy.edu.ar/profile/btabqmiaf/

https://www.rwaq.org/users/vlastazarubina-20250803003626

https://www.band.us/page/99531147/

На сайте https://expertbp.ru/ получите абсолютно бесплатную консультацию от бюро переводов. Здесь вы сможете заказать любую нужную услугу, в том числе, апостиль, нотариальный перевод, перевод свидетельства о браке. Также доступно и срочное оказание услуги. В компании трудятся только лучшие, квалифицированные, знающие переводчики с большим опытом. Услуга будет оказана в ближайшее время. Есть возможность воспользоваться качественным переводом независимо от сложности. Все услуги оказываются по привлекательной цене.

Посетите сайт https://artracam.com/ и вы сможете ознакомиться с Артракам – это эффективный препарат для лечения суставов от производителя. На сайте есть цена и инструкция по применению. Ознакомьтесь со всеми преимуществами данного средства – эффективность Артракама при артрите, при остеоартрозе, при остеохондрозе.

На сайте https://vitamax.shop/ изучите каталог популярной, востребованной продукции «Витамакс». Это – уникальная, популярная линейка ценных и эффективных БАДов, которые улучшают здоровье, дарят прилив энергии, бодрость. Важным моментом является то, что продукция разработана врачом-биохимиком, который потратил на исследования годы. На этом портале представлена исключительно оригинальная продукция, которая заслуживает вашего внимания. При необходимости воспользуйтесь консультацией специалиста, который подберет для вас БАД.

https://sayaumuzuna.bandcamp.com/album/daughter

На сайте https://filmix.fans посмотрите фильмы в отличном качестве. Здесь они представлены в огромном многообразии, а потому точно есть, из чего выбрать. Играют любимые актеры, имеются колоритные персонажи, которые обязательно понравятся вам своей креативностью. Все кино находится в эталонном качестве, с безупречным звуком, а потому обязательно произведет эффект. Для того чтобы получить доступ к большому количеству функций, необходимо пройти регистрацию. На это уйдет пара минут. Представлены триллеры, мелодрамы, драмы и многое другое.

https://hub.docker.com/u/baamigesese

https://hoo.be/pnebybiefufe

https://kemono.im/efxycebod/filippiny-kupit-gashish-boshki-marikhuanu

Ищете, где заказать надежную кухню на заказ по вашим размерам за адекватные деньги? Посмотрите портфолио кухонной фабрики GLORIA – https://gloriakuhni.ru/ – все проекты выполнены в Санкт-Петербурге и области. На каждую кухню гарантия 36 месяцев, более 800 цветовых решений. Большое разнообразие фурнитуры. Удобный онлайн-калькулятор прямо на сайте и понятное формирование цены. Много отзывов клиентов, видео-обзоры кухни с подробностями и деталями. Для всех клиентов – столешница и стеновая панель в подарок.

https://www.band.us/page/99489328/

На сайте https://rusvertolet.ru/ воспользуйтесь возможностью заказать незабываемый, яркий полет на вертолете. Вы гарантированно получите много положительных впечатлений, удивительных эмоций. Важной особенностью компании является то, что полет состоится по приятной стоимости. Вертолетная площадка расположена в городе, а потому просто добраться. Компания работает без выходных, потому получится забронировать полет в любое время. Составить мнение о работе помогут реальные отзывы. Прямо сейчас ознакомьтесь с видами полетов и их расписанием.

https://beteiligung.stadtlindau.de/profile/%D0%9A%D1%83%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%82%D1%8C%20%D0%9A%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%B8%D0%BD%20%D0%9C%D0%B5%D1%84%D0%B5%D0%B4%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%BD%20%D0%9C%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D1%85%D1%83%D0%B0%D0%BD%D1%83%20%D0%A1%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B1%D0%B8%D1%8F/

https://hoo.be/ebycougaf

https://community.wongcw.com/blogs/1124131/%D0%9C%D0%B0%D0%B9%D1%80%D1%85%D0%BE%D1%84%D0%B5%D0%BD-%D0%BA%D1%83%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%82%D1%8C-%D0%9A%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%B8%D0%BD-%D0%AD%D0%BA%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%B7%D0%B8-%D0%91%D0%BE%D1%88%D0%BA%D0%B8

https://potofu.me/lc3ifkkl

https://say.la/read-blog/122765

Ищете рейтинг лучших сервисов виртуальных номеров? Посетите страницу https://blog.virtualnyy-nomer.ru/top-15-servisov-virtualnyh-nomerov-dlya-priema-sms и вы найдете ТОП-15 сервисов виртуальных номеров для приема СМС со всеми их преимуществами и недостатками, а также личный опыт использования.

https://rant.li/1ez7rrri1k

https://potofu.me/073pb7f4

Ищете медицинское оборудование? Agsvv.ru/catalog/obluchateli_dlya_lecheniya/obluchatel_dlya_lecheniya_psoriaza_ultramig_302/ и вы найдете Облучатель ультрафиолетовый Ультрамиг–302М для покупки от производителя, а также сможете ознакомиться со всеми его характеристиками, описанием, преимуществами, отзывами. Узнайте для кого подходит и какие заболевания лечит. Купить от псориаза и иных заболеваний облучатель, а также другую продукцию, вы сможете от производителя – компании Хронос напрямую.

https://www.passes.com/deborah21carter

https://beteiligung.stadtlindau.de/profile/%D0%9A%D1%83%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%82%D1%8C%20%D0%AD%D0%BA%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%B7%D0%B8%20%D0%9C%D0%94%D0%9C%D0%90%20%D0%9A%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%B8%D0%BD%20%D0%A0%D1%83%D0%BC%D1%8B%D0%BD%D0%B8%D1%8F/

https://git.project-hobbit.eu/uuhodignoh

https://potofu.me/va8ks2l6

https://git.project-hobbit.eu/magyfods

https://ucgp.jujuy.edu.ar/profile/ufehufaha/

Интернет магазин электроники «IZICLICK.RU» предлагает высококачественные товары. У нас можете купить: мониторы, принтеры, моноблоки, сканеры и МФУ, ноутбуки, телевизоры и другое. Гарантируем доступные цены и выгодные предложения. Стремимся ваши покупки максимально комфортными сделать. https://iziclick.ru – портал, где вы отыщите подробные описания товара, отзывы, фотографии и характеристики. Предоставим вам профессиональную консультацию и поможем сделать оптимальный выбор. Доставим ваш заказ по Москве и области.

https://ucgp.jujuy.edu.ar/profile/efyygeeoicib/

https://rant.li/fuycibofufub/la-romana-kupit-kokain-mefedron-marikhuanu

https://beteiligung.stadtlindau.de/profile/%D0%9A%D1%83%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%82%D1%8C%20%D0%AD%D0%BA%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%B7%D0%B8%20%D0%9C%D0%94%D0%9C%D0%90%20%D0%9A%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%B8%D0%BD%20%D0%96%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%B0/

https://hoo.be/magufihybdt

На сайте https://iziclick.ru/ в большом ассортименте представлены телевизоры, аксессуары, а также компьютерная техника, приставки, мелкая бытовая техника. Все товары от лучших, проверенных марок, потому отличаются долгим сроком эксплуатации, надежностью, практичностью, простотой в применении. Вся техника поставляется напрямую со склада производителя. Продукция является оригинальной, сертифицированной. Реализуется по привлекательным расценкам, зачастую устраиваются распродажи для вашей большей выгоды.

https://beteiligung.stadtlindau.de/profile/%D0%9A%D1%83%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%82%D1%8C%20%D0%91%D0%BE%D1%88%D0%BA%D0%B8%20%D0%9C%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D1%85%D1%83%D0%B0%D0%BD%D1%83%20%D0%93%D0%B0%D1%88%D0%B8%D1%88%20%D0%9B%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%BD%D0%B0%D0%BA%D0%B0/

https://www.rwaq.org/users/brownmatthias43-20250802221139

https://www.brownbook.net/business/54138818/купить-экстази-кокаин-амфетамин-нарва/

https://www.band.us/page/99530745/

https://say.la/read-blog/123372

Бывают такие ситуации, когда требуется помощь хакеров, которые быстро, эффективно справятся с самой сложной задачей. Специалисты с легкостью взломают почту, взломают пароли, поставят защиту на ваш телефон. Для решения задачи применяются только проверенные, эффективные способы. Любой хакер отличается большим опытом. https://hackerlive.biz – портал, где работают только проверенные, знающие хакеры. За свою работу они не берут большие деньги. Все работы высокого качества. В данный момент напишите тому хакеру, который соответствует предпочтениям.

https://www.band.us/band/99513474/

https://pxlmo.com/hintegalamzy

https://rant.li/igobpice/rovin-kupit-kokain-mefedron-marikhuanu

Посетите сайт https://ambenium.ru/ и вы сможете ознакомиться с Амбениум – единственный нестероидный противовоспалительный препарат зарегистрированный в России с усиленным обезболивающим эффектом – раствор для внутримышечного введения фенилбутазон и лидокаин. На сайте есть цена и инструкция по применению. Ознакомьтесь со всеми преимуществами данного средства.

https://hub.docker.com/u/jenemhaoxin

На сайте https://kino.tartugi.name/kolektcii/garri-potter-kolekciya посмотрите яркий, динамичный и интересный фильм «Гарри Поттер», который представлен здесь в отменном качестве. Картинка находится в высоком разрешении, а звук многоголосый, объемный, поэтому просмотр принесет исключительно приятные, положительные эмоции. Фильм подходит для просмотра как взрослыми, так и детьми. Просматривать получится на любом устройстве, в том числе, мобильном телефоне, ПК, планшете. Вы получите от этого радость и удовольствие.

https://www.band.us/page/99488313/

https://ucgp.jujuy.edu.ar/profile/acgabaidli/

https://git.project-hobbit.eu/fodeaydifui

РусВертолет – компания, которая занимает лидирующие позиции среди конкурентов по качеству услуг и доступной ценовой политики. Работаем 7 дней в неделю. Наш основной приоритет – ваша безопасность. Вертолеты в хорошем состоянии, быстро заказать полет можно на сайте. Обеспечим вам море положительных и ярких эмоций! Ищете прогулка на вертолете нижний новгород? Rusvertolet.ru – тут есть видео и фото полетов, а также отзывы радостных клиентов. Вы узнаете, где мы находимся и как добраться. Подготовили ответы на самые частые вопросы о полетах на вертолете. Всегда вам рады!

На сайте https://selftaxi.ru/ вы сможете задать вопрос менеджеру для того, чтобы узнать всю нужную информацию о заказе минивэнов, микроавтобусов. В парке компании только исправная, надежная, проверенная техника, которая работает отлаженно и никогда не подводит. Рассчитайте стоимость поездки прямо сейчас, чтобы продумать бюджет. Вся техника отличается повышенной вместимостью, удобством. Всегда в наличии несколько сотен автомобилей повышенного комфорта. Прямо сейчас ознакомьтесь с тарифами, которые всегда остаются выгодными.

https://www.band.us/page/99493281/

https://hub.docker.com/u/Mayukimmeskillitu

https://say.la/read-blog/122258

https://community.wongcw.com/blogs/1123294/%D0%9C%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%B4%D0%B6%D0%B8%D0%BC-%D0%BA%D1%83%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%82%D1%8C-%D0%9A%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%B8%D0%BD-%D0%AD%D0%BA%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%B7%D0%B8-%D0%91%D0%BE%D1%88%D0%BA%D0%B8

https://hockeyempire.ru

https://e3-studio.online

https://alar8.online

https://ooo-mitsar.online

https://lenovo-russia.ru

https://glavkupol.ru

https://art-vis.ru

CyberGarden – для приобретения цифрового оборудования наилучшее место. Интернет-магазин предоставляет богатый выбор высококачественной продукции с хорошим сервисом. Вас выгодные цены порадуют. https://cyber-garden.com – здесь можете детально ознакомиться с условиями оплаты и доставки. CyberGarden предоставляет легкий процесс заказа и удобный интерфейс, превращая в удовольствие онлайн-покупки. Для нас бесценно доверие клиентов, поэтому мы к работе с огромной ответственностью подходим. Гарантируем вам профессиональную консультацию.

https://alar8.online

https://treneramo.online

https://itravel-vl.ru

https://integral-msk.ru

https://art-of-pilates.ru

https://ltalfa.ru

T.me/m1xbet_ru – канал проекта 1Xbet официальный. Здесь исключительно важная информация представлена. Многие считают 1Xbet одним из наилучших букмекеров. Платформа имеет интуитивно понятную навигацию, дарит яркие эмоции и, конечно же, азарт. Специалисты службы поддержки при необходимости всегда готовы помочь. https://t.me/m1xbet_ru – здесь представлены отзывы игроков о 1xBET. Платформа с помощью актуальных акций старается пользователей удерживать. Вывод средств проходит без проблем. Все четко и быстро работает. Удачных ставок!

https://art-vis.ru

https://citywolf.online

https://vintage-nsk.online

На сайте https://papercloud.ru/ вы отыщете материалы на самые разные темы, которые касаются финансов, бизнеса, креативных идей. Ознакомьтесь с самыми актуальными трендами, тенденциями из сферы аналитики и многим другим. Только на этом сайте вы найдете все, что нужно, чтобы правильно вести процветающий бизнес. Ознакомьтесь с выбором редакции, пользователей, чтобы быть осведомленным в многочисленных вопросах. Представлена информация, которая касается капитализации рынка криптовалюты. Опубликованы новые данные на тему бизнеса.

https://cashparfum.ru

На сайте https://eliseevskiydom.ru/ изучите номера, один из которых вы сможете забронировать в любое, наиболее комфортное время. Это – возможность устроить уютный, комфортный и незабываемый отдых у Черного моря. Этот дом находится в нескольких минутах ходьбы от пляжа. Здесь вас ожидает бесплатный интернет, просторные и вместительные номера, приятная зеленая терраса, сад. Для того чтобы быстрее принять решение о бронировании, изучите фотогалерею. Имеются номера как для семейных, так и тех, кто прибыл на отдых один.

https://e3-studio.online

На сайте https://selftaxi.ru/miniven6 закажите такси минивэн, которое прибудет с водителем. Автобус рассчитан на 6 мест, чтобы устроить приятную поездку как по Москве, так и области. Это комфортабельный, удобный для передвижения автомобиль, на котором вы обязательно доедете до нужного места. Перед рейсом он обязательно проверяется, проходит технический осмотр, а в салоне всегда чисто, ухоженно. А если вам необходимо уточнить определенную информацию, то укажите свои данные, чтобы обязательно перезвонил менеджер и ответил на все вопросы.

https://alar8.online

https://ooo-mitsar.online

https://ooo-mitsar.online

https://respublika1.online

https://vlgprestol.online

https://kanscity.online

https://citywolf.online

На сайте https://seobomba.ru/ ознакомьтесь с информацией, которая касается продвижения ресурса вечными ссылками. Эта компания предлагает воспользоваться услугой, которая с каждым годом набирает популярность. Получится продвинуть сайты в Google и Яндекс. Эту компанию выбирают по причине того, что здесь используются уникальные, продвинутые методы, которые приводят к положительным результатам. Отсутствуют даже незначительные риски, потому как в работе используются только «белые» методы. Тарифы подойдут для любого бюджета.

https://belovahair.online

https://orientirum.online

https://belovahair.online

https://respublika1.online

https://crovlyagrad.online

https://oknapsk.online

https://treneramo.online

Посетите сайт https://cs2case.io/ и вы сможете найти кейсы КС (КС2) в огромном разнообразии, в том числе и бесплатные! Самый большой выбор кейсов кс го у нас на сайте. Посмотрите – вы обязательно найдете для себя шикарные варианты, а выдача осуществляется моментально к себе в Steam.

https://orientirum.online

https://crovlyagrad.online

https://vintage-nsk.online

https://respublika1.online

https://pxlmo.com/muffincreepecraft2

https://ucgp.jujuy.edu.ar/profile/ohahygiydrid/

https://www.brownbook.net/business/54151526/шибеник-кокаин-мефедрон-марихуана/

На сайте https://vc.ru/crypto/2132042-obmen-usdt-v-kaliningrade-kak-bezopasno-i-vygodno-obnalichit-kriptovalyutu ознакомьтесь с полезной и важной информацией относительно обмена USDT. На этой странице вы узнаете о том, как абсолютно безопасно, максимально оперативно произвести обналичивание криптовалюты. Сейчас она используется как для вложений, так и международных расчетов. Ее выдают в качестве заработной платы, используется для того, чтобы сохранить сбережения. Из статьи вы узнаете и то, почему USDT является наиболее востребованной валютой.

https://allmynursejobs.com/author/mamouttumbe/

https://www.brownbook.net/business/54151633/берлин-амфетамин-кокаин-экстази/

https://wanderlog.com/view/lbewvztadu/

Компания Авангард качественные услуги предоставляет. У нас работают профессионалы своего дела. Мы в обучение персонала вкладываемся. Производим и поставляем детали для предприятий машиностроения, медицинской и авиационной промышленности. https://avangardmet.ru – тут представлена о компании более детальная информация. Все сотрудники имеют высшее образование и повышают свою квалификацию. Закупаем оборудование новое и качество продукции гарантируем. При возникновении вопросов, звоните нам по телефону.

https://odysee.com/@meSayokofours

https://www.band.us/page/99566912/

https://pxlmo.com/kiddomatteopowell4

https://beteiligung.stadtlindau.de/profile/%D0%9A%D1%83%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%82%D1%8C%20%D0%AD%D0%BA%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%B7%D0%B8%20%D0%9C%D0%94%D0%9C%D0%90%20%D0%9A%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%B8%D0%BD%20%D0%91%D1%8B%D0%B4%D0%B3%D0%BE%D1%89/

https://allmynursejobs.com/author/luteyreverts/

На сайте https://pet4home.ru/ представлена содержательная, интересная информация на тему животных. Здесь вы найдете материалы о кошках, собаках и правилах ухода за ними. Имеются данные и об экзотических животных, птицах, аквариуме. А если ищете что-то определенное, то воспользуйтесь специальным поиском. Регулярно на портале выкладываются любопытные публикации, которые будут интересны всем, кто держит дома животных. На портале есть и видеоматериалы для наглядности. Так вы узнаете про содержание, питание, лечение животных и многое другое.

Типография «Изумруд Принт» на цифровой печати специализируется. Мы несем ответственность за изготовленную продукцию, ориентируемся только на высокие стандарты. Выполняем заказы оперативно и без задержек. Ценим ваше время! Ищете печать полиграфии? Izumrudprint.ru – здесь вы можете ознакомиться с нашими услугами. С радостью ответим на интересующие вас вопросы. Гарантируем доступные цены и добиваемся наилучших результатов. Прислушиваемся ко всем пожеланиям заказчиков. Если вы к нам обратитесь, то верного друга и надежного партнера обретете.

https://potofu.me/l1avjm7f

https://hub.docker.com/u/sikoshrongy

https://beteiligung.stadtlindau.de/profile/%D0%9A%D1%83%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%82%D1%8C%20%D0%91%D0%BE%D1%88%D0%BA%D0%B8%20%D0%9C%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D1%85%D1%83%D0%B0%D0%BD%D1%83%20%D0%93%D0%B0%D1%88%D0%B8%D1%88%20%D0%A1%D0%B0%D0%BB%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%BA%D0%B8/

https://community.wongcw.com/blogs/1128537/%D0%91%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%82%D0%B8%D1%81%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%B2%D0%B0-%D0%90%D0%BC%D1%84%D0%B5%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BC%D0%B8%D0%BD-%D0%9A%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%B8%D0%BD-%D0%AD%D0%BA%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%B7%D0%B8

https://estinsnackbj.bandcamp.com/album/block

https://hoo.be/abygygzc

На сайте https://gorodnsk63.ru/ ознакомьтесь с интересными, содержательными новостями, которые касаются самых разных сфер, в том числе, экономики, политики, бизнеса, спорта. Узнаете, что происходит в Самаре в данный момент, какие важные события уже произошли. Имеется информация о высоких технологиях, новых уникальных разработках. Все новости сопровождаются картинками, есть и видеорепортажи для большей наглядности. Изучите самые последние новости, которые выложили буквально час назад.

https://muckrack.com/person-27431802

https://wanderlog.com/view/mzggxnmpln/

Посетите сайт https://god2026.com/ и вы сможете качественно подготовится к Новому году 2026 и почитать любопытную информацию: о символе года Красной Огненной Лошади, рецепты на Новогодний стол 2026 и как украсить дом, различные приметы в Новом 2026 году и многое другое. Познавательный портал где вы найдете многое!

https://ucgp.jujuy.edu.ar/profile/ecubueefef/

https://potofu.me/smy8hzh9

https://potofu.me/5hs8hoy1

https://potofu.me/48kojrjn

На сайте https://sberkooperativ.ru/ изучите увлекательные, интересные и актуальные новости на самые разные темы, в том числе, банки, финансы, бизнес. Вы обязательно ознакомитесь с экспертным мнением ведущих специалистов и спрогнозируете возможные риски. Изучите информацию о реформе ОСАГО, о том, какие решения принял ЦБ, мнение Трампа на самые актуальные вопросы. Статьи добавляются регулярно, чтобы вы ознакомились с самыми последними данными. Для вашего удобства все новости поделены на разделы, что позволит быстрее сориентироваться.

https://www.montessorijobsuk.co.uk/author/xohoecad/

https://wanderlog.com/view/lfkywbjday/

На сайте https://vless.art воспользуйтесь возможностью приобрести ключ для VLESS VPN. Это ваша возможность обеспечить себе доступ к качественному, бесперебойному, анонимному Интернету по максимально приятной стоимости. Вашему вниманию удобный, простой в понимании интерфейс, оптимальная скорость, полностью отсутствуют логи. Можно запустить одновременно несколько гаджетов для собственного удобства. А самое важное, что нет ограничений. Приобрести ключ получится даже сейчас и радоваться отменному качеству, соединению.

https://community.wongcw.com/blogs/1128583/%D0%9C%D0%B0%D0%B2%D1%80%D0%B8%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%B9-%D0%90%D0%BC%D1%84%D0%B5%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BC%D0%B8%D0%BD-%D0%9A%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%B8%D0%BD-%D0%AD%D0%BA%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%B7%D0%B8

https://muckrack.com/person-27417264

Сайт https://xn--e1anbce0ah.xn--p1ai/ представляет собой сервис, который предоставляет возможность обменять криптовалюту. Каждый клиент получает возможность произвести обмен Ethereum, Bitcoin, SOL, BNB, XRP на наличные. Основная специализация компании заключается в том, чтобы предоставить быстрый и надлежащий доступ ко всем функциям, цифровым активам. Причем независимо от того, в каком городе либо стране находитесь. Прямо сейчас вы сможете посчитать то, сколько вы получите после обмена. Узнайте подробности о денежных перестановках.

https://paper.wf/iycycjagha/korfu-kupit-gashish-boshki-marikhuanu

https://hoo.be/radubwefs

На сайте https://hackerlive.biz вы найдете профессиональных, знающих и талантливых хакеров, которые окажут любые услуги, включая взлом, защиту, а также использование уникальных, анонимных методов. Все, что нужно – просто связаться с тем специалистом, которого вы считаете самым достойным. Необходимо уточнить все важные моменты и расценки. На форуме есть возможность пообщаться с единомышленниками, обсудить любые темы. Все специалисты квалифицированные и справятся с работой на должном уровне. Постоянно появляются новые специалисты, заслуживающие внимания.

https://rant.li/edaadefi/chendu-kupit-gashish-boshki-marikhuanu

https://www.rwaq.org/users/prokillmrgood637-20250808145234

https://odysee.com/@ToddSolomonTod

https://www.montessorijobsuk.co.uk/author/locygogicli/

https://www.band.us/page/99563599/

https://say.la/read-blog/123646

https://odysee.com/@lahdoliplap

https://odysee.com/@pomelosorge

https://community.wongcw.com/blogs/1128290/%D0%94%D1%8C%D1%91%D1%80-%D0%9A%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%B8%D0%BD-%D0%9C%D0%B5%D1%84%D0%B5%D0%B4%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%BD-%D0%9C%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D1%85%D1%83%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B0

https://www.band.us/page/99563251/

https://say.la/read-blog/123910

https://git.project-hobbit.eu/johicuediygb

Посетите сайт https://ambenium.ru/ и вы сможете ознакомиться с Амбениум – единственный нестероидный противовоспалительный препарат зарегистрированный в России с усиленным обезболивающим эффектом – раствор для внутримышечного введения фенилбутазон и лидокаин. На сайте есть цена и инструкция по применению. Ознакомьтесь со всеми преимуществами данного средства.

Инпек с успехом производит красивые и надежные шильдики из металла. Справляемся с самыми сложными задачами гравировки. Гарантируем соблюдение сроков. Свяжитесь с нами, расскажите о своих пожеланиях и требованиях. Вместе придумаем, как сделать то, что необходимо вам действительно. https://inpekmet.ru – здесь представлены примеры лазерной гравировки. В своей работе мы уверены. Применяем только новейшее оборудование высокоточное. Предлагаем заманчивые цены. Будем рады вас среди наших постоянных клиентов видеть.

https://www.brownbook.net/business/54152843/италия-марихуана-гашиш-канабис/

https://say.la/read-blog/124114

https://potofu.me/nof7xvxf

https://say.la/read-blog/124144

https://fahaddyawat.bandcamp.com/album/bale

https://git.project-hobbit.eu/thuhifsfobyg

https://pxlmo.com/suthalretzep

https://www.band.us/page/99544496/

https://www.themeqx.com/forums/users/mafpucac/

https://www.band.us/band/99544686/

https://allmynursejobs.com/author/ruby-mary05021997/

По ссылке https://vc.ru/crypto/2132102-obmen-usdt-v-nizhnem-novgorode-podrobnyi-gid-v-2025-godu почитайте информацию про то, как обменять USDT в городе Нижнем Новгороде. Перед вами самый полный гид, из которого вы в подробностях узнаете о том, как максимально безопасно, быстро произвести обмен USDT и остальных популярных криптовалют. Есть информация и о том, почему выгодней сотрудничать с профессиональным офисом, и почему это считается безопасно. Статья расскажет вам и о том, какие еще криптовалюты являются популярными в Нижнем Новгороде.

https://allmynursejobs.com/author/luziboehon/

https://www.themeqx.com/forums/users/leoyficu/

https://www.band.us/page/99563009/

https://odysee.com/@nharszuchy

https://say.la/read-blog/123702

На сайте https://sprotyv.org/ представлено огромное количество интересной, актуальной и содержательной информации на самую разную тему: экономики, политики, войны, бизнеса, криминала, культуры. Здесь только самая последняя и ценная информация, которая будет важна каждому, кто проживает в этой стране. На портале регулярно появляются новые публикации, которые ответят на многие вопросы. Есть информация на тему здоровья и того, как его поправить, сохранить до глубокой старости.

На сайте https://yagodabelarusi.by уточните информацию о том, как вы сможете приобрести саженцы ремонтантной либо летней малины. В этом питомнике только продукция высокого качества и премиального уровня. Именно поэтому вам обеспечены всходы. Питомник предлагает такие саженцы, которые позволят вырастить сортовую, крупную малину для коммерческих целей либо для собственного употребления. Оплатить покупку можно наличным либо безналичным расчетом. Малина плодоносит с июля и до самых заморозков. Саженцы отправляются Европочтой либо Белпочтой.

https://www.brownbook.net/business/54154028/альмерия-кокаин-мефедрон-марихуана/

https://ucgp.jujuy.edu.ar/profile/ieflqfubi/

https://bio.site/aafeybedufe

https://rant.li/ebegveabi/okinava-kupit-kokain-mefedron-marikhuanu

https://beteiligung.stadtlindau.de/profile/%D0%9A%D1%83%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%82%D1%8C%20%D0%91%D0%BE%D1%88%D0%BA%D0%B8%20%D0%9C%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D1%85%D1%83%D0%B0%D0%BD%D1%83%20%D0%93%D0%B0%D1%88%D0%B8%D1%88%20%D0%A7%D0%B5%D1%85%D0%B8%D1%8F/

https://rant.li/nidobegcqohj/milan-kupit-kokain-mefedron-marikhuanu

https://wanderlog.com/view/shhidmjsdp/

СХТ-Москва – компания, которая железнодорожные, карьерные, автомобильные и складские весы предлагает. Продукция соответствует новейшим требованиям по надежности и точности. Гарантируем оперативные сроки производства весов. https://moskva.cxt.su/products/avtomobilnye-vesy/ – здесь представлена видео-презентация о компании СХТ. На ресурсе узнаете, как изготовление весов происходит. Придерживаемся лояльной ценовой политики и предоставляем широкий ассортимент продукции. Стремимся удовлетворить потребности и требования наших клиентов.

https://allmynursejobs.com/author/sasminibriqi/

https://www.montessorijobsuk.co.uk/author/ohqeuuocqxub/

На сайте https://feringer.shop/ воспользуйтесь возможностью приобрести печи высокого качества для саун, бань. Все они надежные, практичные, простые в использовании и обязательно впишутся в общую концепцию. В каталоге вы найдете печи для сауны, бани, дымоходы, порталы ламель, дымоходы стартовые. Регулярно появляются новинки по привлекательной стоимости. Важной особенностью печей является то, что они существенно понижают расход дров. Печи Ферингер отличаются привлекательным внешним видом, длительным сроком эксплуатации.

https://paper.wf/dihufhydqia/naksos-kupit-ekstazi-mdma-lsd-kokain

https://git.project-hobbit.eu/yoybocxpyg

https://beteiligung.stadtlindau.de/profile/%D0%9A%D1%83%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%82%D1%8C%20%D0%91%D0%BE%D1%88%D0%BA%D0%B8%20%D0%9C%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D1%85%D1%83%D0%B0%D0%BD%D1%83%20%D0%93%D0%B0%D1%88%D0%B8%D1%88%20%D0%91%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8/

https://potofu.me/9oo8uboj

https://www.montessorijobsuk.co.uk/author/gocdegybeh/

https://hoo.be/bacigyguf

На сайте https://selftaxi.ru/miniven6 закажите такси минивэн, которое прибудет с водителем. Автобус рассчитан на 6 мест, чтобы устроить приятную поездку как по Москве, так и области. Это комфортабельный, удобный для передвижения автомобиль, на котором вы обязательно доедете до нужного места. Перед рейсом он обязательно проверяется, проходит технический осмотр, а в салоне всегда чисто, ухоженно. А если вам необходимо уточнить определенную информацию, то укажите свои данные, чтобы обязательно перезвонил менеджер и ответил на все вопросы.

https://hub.docker.com/u/uOlivanlif3skill

https://paper.wf/hvbzayyg/tampere-kupit-ekstazi-mdma-lsd-kokain

https://allmynursejobs.com/author/hernandez_patriciaw27219/

https://bio.site/pkocyyhofpvo

https://potofu.me/p0nowy81

https://pxlmo.com/headlessrealistics

https://www.montessorijobsuk.co.uk/author/ycyfedaocig/

На сайте https://chisty-list.ru/ узнайте стоимость уборки конкретно вашего объекта. Но в любом случае она будет умеренной. Специально для вас профессиональный клининг квартиры, офиса. Есть возможность воспользоваться генеральной уборкой либо послестроительной. Если есть вопросы, то воспользуйтесь консультацией, обозначив свои данные в специальной форме. Вы получите гарантию качества на все услуги, потому как за каждым объектом закрепляется менеджер. Все клинеры являются проверенными, опытными, используют профессиональный инструмент.

https://muckrack.com/person-27434954

https://bio.site/kyacqugy

https://pxlmo.com/trappey77hurst

https://potofu.me/ugubtbjw

https://hub.docker.com/u/rociookhanan

На сайте https://veronahotel.pro/ спешите забронировать номер в популярном гостиничном комплексе «Верона», который предлагает безупречный уровень обслуживания, комфортные и вместительные номера, в которых имеется все для проживания. Представлены номера «Люкс», а также «Комфорт». В шаговой доступности находятся крупные торговые центры. Все гости, которые останавливались здесь, оставались довольны. Регулярно проходят выгодные акции, действуют скидки. Ознакомьтесь со всеми доступными для вас услугами.

https://rant.li/uoghobagyidy/dokha-kupit-kokain-mefedron-marikhuanu

https://rant.li/qnnlsukfns

https://potofu.me/am26366f

https://hoo.be/zpacefedefuh

https://potofu.me/hdtd63wa

https://odysee.com/@marinadaisy09

https://www.montessorijobsuk.co.uk/author/ehczvebtyb/

https://say.la/read-blog/124052

https://www.montessorijobsuk.co.uk/author/lgeibihu/

https://potofu.me/jcogn66q

https://paper.wf/ohdahycuy/bil-bao-kupit-gashish-boshki-marikhuanu

https://community.wongcw.com/blogs/1128550/%D0%91%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%BD-%D0%90%D0%BC%D1%84%D0%B5%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BC%D0%B8%D0%BD-%D0%9A%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%B8%D0%BD-%D0%AD%D0%BA%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%B7%D0%B8

https://paper.wf/jbygtpyhuh/liberets-kupit-ekstazi-mdma-lsd-kokain

https://www.metooo.io/u/689779aa059d68282f0c639a

Посетите сайт https://karmicstar.ru/ и вы сможете рассчитать бесплатно Кармическую звезду по дате рождения. Кармический калькулятор поможет собрать свою конфигурацию кармических треугольников к расшифровке, либо выбрать к распаковке всю кармическую звезду и/или проверить совместимость пары по дате рождения. Подробнее на сайте.

https://community.wongcw.com/blogs/1128302/%D0%91%D0%B0%D0%BA%D1%83-%D0%9A%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%B8%D0%BD-%D0%9C%D0%B5%D1%84%D0%B5%D0%B4%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%BD-%D0%9C%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D1%85%D1%83%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B0

https://allmynursejobs.com/author/tiffanykpearl05/

debaltsevoty.ru

На сайте https://us-atlas.com/ изучите атлас как Южной, так и Северной Америки в самых мельчайших подробностях. Все карты отличаются безупречной детализацией. Перед вами самые подробные и большие географические карты, которые помогут расширить мировоззрение и лучше изучить страны. Здесь вы найдете все, что нужно, чтобы составить правильное впечатление. Все карты, которые находятся на этом сайте, можно легко напечатать. Есть не только города, но и небольшие поселения, провинции, с которыми ознакомится каждый желающий.

volnovaxave.ru

По ссылке https://dtf.ru/ask/3936354-kak-izbezhat-p2p-treugolnika вы отыщете важную и полезную информацию, касающуюся того, как обойти P2P-треугольник. Перед вами самое полное, исчерпывающее руководство, которое прольет свет на многие вопросы. P2P-арбитраж примечателен тем, что позволяет существенно заработать на разнице криптовалют. Но иногда попадают в мошенническую схему. И тогда вы не только потеряете финансы, но и есть вероятность того, что карту заблокируют. Из статьи вы узнаете о том, что представляет собой P2P-треугольник, как работает. Ознакомитесь и с пошаговой механикой такой схемы.

gorlovkaler.ru

enakievofel.ru

yasinovatayate.ru

На сайте https://moregam.ru представлен огромный выбор игр, а также приложений, которые идеально подходят для Android. Прямо сейчас вы получаете возможность скачать АРК, ознакомиться с содержательными, информативными обзорами. Регулярно появляются увлекательные новинки, которые созданы на русском языке. Перед вами огромный выбор вариантов, чтобы разнообразить досуг. При этом вы можете выбрать игру самого разного жанра. Вы точно не заскучаете! Здесь представлены аркады, увлекательные викторины, головоломки, гонки.

gorlovkaler.ru

debaltsevoty.ru

Bonjour, fans de casinos en ligne !

Si vous voulez tout savoir sur les plateformes en France, alors c’est un bon plan.

Consultez l’integralite via le lien en piece jointe :

https://sugarcaneventures.com/casino-en-ligne-france-345/

mariupolol.ru

dokuchaevsked.ru

mariupolol.ru

antracitfel.ru

debaltsevoer.ru

debaltsevoer.ru

mariupolper.ru

alchevskter.ru

enakievoler.ru

debaltsevoer.ru

volnovaxave.ru

gorlovkaler.ru

dokuchaevskul.ru

На сайте https://eliseevskiydom.ru/ изучите номера, один из которых вы сможете забронировать в любое, наиболее комфортное время. Это – возможность устроить уютный, комфортный и незабываемый отдых у Черного моря. Этот дом находится в нескольких минутах ходьбы от пляжа. Здесь вас ожидает бесплатный интернет, просторные и вместительные номера, приятная зеленая терраса, сад. Для того чтобы быстрее принять решение о бронировании, изучите фотогалерею. Имеются номера как для семейных, так и тех, кто прибыл на отдых один.

debaltsevoty.ru

volnovaxaber.ru

mariupolper.ru

Rz-Work – биржа для опытных профессионалов и новичков, которые к ответственной работе готовы. Популярность у фриланс-сервиса высокая. Преимущества, которые выделили пользователи: легкость регистрации, гарантия безопасности сделок, быстрое реагирование службы поддержки. https://rz-work.ru – тут более детальная информация представлена. Rz-Work является платформой, которая способствует эффективному взаимодействию заказчиков и исполнителей. Она понятным интерфейсом отличается. Площадка многопрофильная, она много категорий охватывает.

enakievoler.ru

alchevskhoe.ru

yasinovatayate.ru

debaltsevoer.ru

volnovaxave.ru

mariupolper.ru

alchevskhoe.ru

На сайте https://cvetochnik-doma.ru/ вы найдете полезную информацию, которая касается комнатных растений, ухода за ними. На портале представлена информация о декоративно-лиственных растениях, суккулентах. Имеются материалы о цветущих растениях, папоротниках, пальмах, луковичных, экзотических, вьющихся растениях, орхидеях. Для того чтобы найти определенную информацию, воспользуйтесь специальным поиском, который подберет статью на основе запроса. Для большей наглядности статьи сопровождаются красочными фотографиями.

yasinovatayahe.ru

debaltsevoty.ru

alchevskter.ru

alchevskhoe.ru

volnovaxaber.ru

https://rant.li/vafjjuucho/varadero-kupit-ekstazi-mdma-lsd-kokain

https://kemono.im/mogugefybubu/saranda-kupit-kokain-mefedron-marikhuanu

Сайт https://interaktivnoe-oborudovanie.ru/ – это оборудование для бизнеса и учебных заведений по выгодной стоимости. У нас: интерактивное оборудование, проекционное оборудование, видео стены, профессиональные панели, информационные киоски и многое другое. Ознакомьтесь с нашим существенным каталогом!

Your blog is a standout of thought-provoking ideas that always spark curiosity and reflection. It would be intriguing to see you examine how these concepts intertwine with emerging trends such as artificial intelligence or sustainable living. Your knack for drawing parallels is truly captivating. Thank you for consistently delivering such rewarding content—I’m excited for what’s next!

Go to: https://talkchatgpt.com/

джпт чат на русском

Посетите сайт https://rivanol-rf.ru/ и вы сможете ознакомиться с Риванол – это аптечное средство для ухода за кожей. На сайте есть цена и инструкция по применению. Ознакомьтесь со всеми преимуществами данного средства, которое содержит уникальный антисептик, регенератор кожи: этакридина лактат.

https://pxlmo.com/xstoreiwani

https://www.rwaq.org/users/vokalyudiat-20250810195650

https://bio.site/duouduybyde

https://pixelfed.tokyo/motloiajeen

https://hoo.be/tycygugocioc

https://say.la/read-blog/124570

https://jhonzshudi.bandcamp.com/album/ammunition

https://rant.li/igecyogzydag/shvetsiia-kupit-kokain-mefedron-marikhuanu

https://bio.site/ludugibjog

На сайте https://prometall.shop/ представлен огромный ассортимент чугунных печей стильного, привлекательного дизайна. За счет того, что выполнены из надежного, прочного и крепкого материала, то наделены долгим сроком службы. Вы сможете воспользоваться огромным спектром нужных и полезных дополнительных услуг. В каталоге вы найдете печи в сетке, камне, а также отопительные. Все изделия наделены компактными размерами, идеально впишутся в любой интерьер. При разработке были использованы уникальные, высокие технологии.

https://rant.li/aihidugade/khurgada-kupit-gashish-boshki-marikhuanu

Посетите сайт https://cs2case.io/ и вы сможете найти кейсы КС (КС2) в огромном разнообразии, в том числе и бесплатные! Самый большой выбор кейсов кс го у нас на сайте. Посмотрите – вы обязательно найдете для себя шикарные варианты, а выдача осуществляется моментально к себе в Steam.

https://www.themeqx.com/forums/users/rbuhigycyci/

https://www.band.us/page/99582307/

https://kemono.im/acoyfaadwac/ingol-shtadt-kupit-gashish-boshki-marikhuanu

https://bio.site/jyhoehodo

https://kemono.im/tgehiagcuo/portugaliia-kupit-kokain-mefedron-marikhuanu

https://www.themeqx.com/forums/users/iydobnnxihvo/

https://bio.site/uhoguogcroy

На сайте http://gotorush.ru воспользуйтесь возможностью принять участие в эпичных, зрелищных турнирах 5х5 и сразиться с остальными участниками, командами, которые преданы своему делу. Регистрация для каждого участника является абсолютно бесплатной. Изучите информацию о последних турнирах и о том, в каких форматах они проходят. Есть возможность присоединиться к команде или проголосовать за нее. Представлен раздел с последними результатами, что позволит сориентироваться в поединках. При необходимости задайте интересующий вопрос службе поддержки.

На сайте https://vc.ru/crypto/2131965-fishing-skam-feikovye-obmenniki-polnyi-gaid-po-zashite-ot-kripto-moshennikov изучите информацию, которая касается фишинга, спама, фейковых обменников. На этом портале вы ознакомитесь с полным гайдом, который поможет вас защитить от мошеннических действий, связанных с криптовалютой. Перед вами экспертная статья, которая раскроет множество секретов, вы получите огромное количество ценных рекомендаций, которые будут полезны всем, кто имеет дело с криптовалютой.

https://say.la/read-blog/125113

http://webanketa.com/forms/6mrk4e1p6gqpccsm74s34dv2/

https://potofu.me/gnfnwoh6

https://pixelfed.tokyo/roorookotuk1992

https://pixelfed.tokyo/razeqdadva

https://www.metooo.io/u/689a3de8c6fd1a348a4040b6

https://www.band.us/page/99595653/

Discover Your Perfect Non GamStop Casinos Experience – https://vaishakbelle.com/ ! Tired of GamStop restrictions? Non GamStop Casinos offer a thrilling alternative for UK players seeking uninterrupted gaming fun. Enjoy a vast selection of top-quality games, generous bonuses, and seamless deposits & withdrawals. Why choose us? No GamStop limitations, Safe & secure environment, Exciting game variety, Fast payouts, 24/7 support. Unlock your gaming potential now! Join trusted Non GamStop Casinos and experience the ultimate online casino adventure. Sign up today and claim your welcome bonus!

Посетите сайт https://rostbk.com/ – где РостБизнесКонсалт приглашает пройти дистанционное обучение без отрыва от производства по всей России: индивидуальный график, доступные цены, короткие сроки обучения. Узнайте на сайте все программы по которым мы проводим обучение, они разнообразны – от строительства и IT, до медицины и промышленной безопасности – всего более 2000 программ. Подробнее на сайте.

https://www.brownbook.net/business/54160800/лозанна-купить-амфетамин-кокаин-экстази/

https://git.project-hobbit.eu/uugifygud

https://www.montessorijobsuk.co.uk/author/lugiudeac/

https://allmynursejobs.com/author/yugaellex/

https://www.band.us/page/99578057/

https://community.wongcw.com/blogs/1129141/%D0%A2%D0%B8%D0%BB%D0%B1%D1%83%D1%80%D0%B3-%D0%9A%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%B8%D0%BD-%D0%9C%D0%B5%D1%84%D0%B5%D0%B4%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%BD-%D0%9C%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B8%D1%85%D1%83%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B0

https://beteiligung.stadtlindau.de/profile/%D0%9A%D1%83%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%82%D1%8C%20%D0%AD%D0%BA%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%B7%D0%B8%20%D0%9C%D0%94%D0%9C%D0%90%20%D0%9A%D0%BE%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%B8%D0%BD%20%D0%9F%D1%83%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%BD/

https://odysee.com/@dorevergirl668

https://potofu.me/ddad9sq7

Посетите сайт https://god2026.com/ и вы сможете качественно подготовится к Новому году 2026 и почитать любопытную информацию: о символе года Красной Огненной Лошади, рецепты на Новогодний стол 2026 и как украсить дом, различные приметы в Новом 2026 году и многое другое. Познавательный портал где вы найдете многое!

Si vous cherchez des sites fiables en France, alors c’est un bon plan.

Decouvrez l’integralite via le lien ci-dessous :

https://ibpsa.es/casino-en-ligne-france-170/

https://www.montessorijobsuk.co.uk/author/keduddyco/